What We Talk About When We Talk About Sex

My friend Will Crawley has a story about a BBC investigation into pornography profits; his particular angle is the role that the Christian Brothers Investment Services, one of the biggest investors of official 'Catholic money' in the world, plays in bolstering the porn industry. Apparently the guidelines for investment are easily made flexible - and so the CBIS apparently has a hefty wad of cash wrapped up in the production of money shots. According to Will: "A spokesperson for CBIS told the BBC Hardcore Profits programme that they aim to influence the moral direction of companies in which they have investments. He also suggested that their policy is a common sense response to the world we live in: any Catholic who believes its right to completely withdraw from any company making any profits from pornography would have to switch off their internet supply, avoid most of the world's hotels, and stop watching television."

The spokesman makes a reasonable point; but the world of 'ethical' investing is always subject to this kind of parsing. Will once reminded me that there's only one answer to the 'Well, where would you draw the line?' when it's posed as a means to doing nothing, a kind of 'Via Apathy'. The answer, of course, is 'SOMEWHERE'. Nothing is done perfectly; but it must be done.

More after the fold

I recall that the Presbyterian Church in Ireland used to define its ethical investment policy as keeping its funds out of alcohol, tobacco, and gambling; but it was ok to have shares in missiles. Pressure from, among others, my friend journalist Mark McCleary helped encourage them to withdraw the blood money, and a new line was drawn. It will need to be drawn again, and again; as more information emerges and our understanding of economics and justice develops. But at least they're trying to draw it somewhere.

I'm not sure where the line should be in the CBIS story; here's an attempt.

1: It makes sense to strive for ethical investment policies to be comprehensive. I'm not particularly troubled by whether or not a church invests in alcohol, and tobacco used to be ok to me, partly because of Wendell Berry (although I'm fast becoming an annoying former smoking evangelist; the odd decent cigar aside); but gambling is self-evidently a trap that the rich can play with while mostly insulated from its sorrows, while the million-to-one lottery winners become idealised scapegoats on which the poor can project fantasies of escape that lead, in the cases of the rest of the million, to perpetuated poverty. So I'm with the PCI two-thirds of the way; and while not investing in alcohol seems a bit strange, given Jesus' early role as a wine merchant, I understand the cultural and socio-economic reasons for divestment.

2: As for porn and weapons, well...It seems to me that there's at least as clear a case for churches refusing to invest in militarism and the 'defence' industry as in pornography. I have a friend whose job used to be to design computer guidance technology that would help direct missiles toward their targets; he left that job to become a pastor, thank God. My view is that a philosophy that values human life - whether of the religious or secular kind inexorably leads to non-participation in the mechanisms of war; because we take life so seriously that it prevents us from playing a part in its destruction by building weapons.

(This does not mean that I believe a religious or secular humanist should under no circumstances join the armed forces; I haven't come to a full conclusion about this yet; but Logan Laituri's thoughtful post 'Prepared to Die, But Not to Kill' raises the issues far better than I could.) Now an argument for pacifism, or neo-pacifism, is made elsewhere on this blog; for now, I guess it just seems that the damage done by explosions is pretty objectively measurable; while porn is just something we're supposed to be disgusted at for nebulous reasons that, it seems to me, are more complex than the friendly mavens of either conservatism or hedonism would like.

3: One of my best friends used to direct porn movies. It was a job; and I have no idea what he felt about it, as I've never asked. But his example is merely one part of a multi-faceted web of supply and demand involving the - presumably universal - desire for the eroticised human body. Sure, I'm aware of the arguments about the exploitation inherent to porn - and I'll take them further; it's not just the participants who may be allowing some of their souls to leak - but we, the viewers, might be giving something of our own dignity away when we watch. Deeper than all of this, however, is the central point I wish to make: There's a reason religious institutions are preoccupied with pornography; and it's the fact that religious institutions are often, quite simply obsessed with sexuality. In that sense, the fact that some of us often get worked up about pornography is a good thing: at least we're talking about sex.

Well, of course, we're not really talking about sex; we're making assumptions about the human body, about there being constitutional differences between religious adherents and other people, about women and men, about what is right and wrong. Some of these assumptions make a lot of sense to me - but not for traditionally conservative moral reasons. It makes sense to me that human beings are made for something more than self-gratification; it makes sense to me that we are not here to be exploited by each other, nor are we made for objectification. Religious institutions not investing in pornography thus makes a lot of sense.

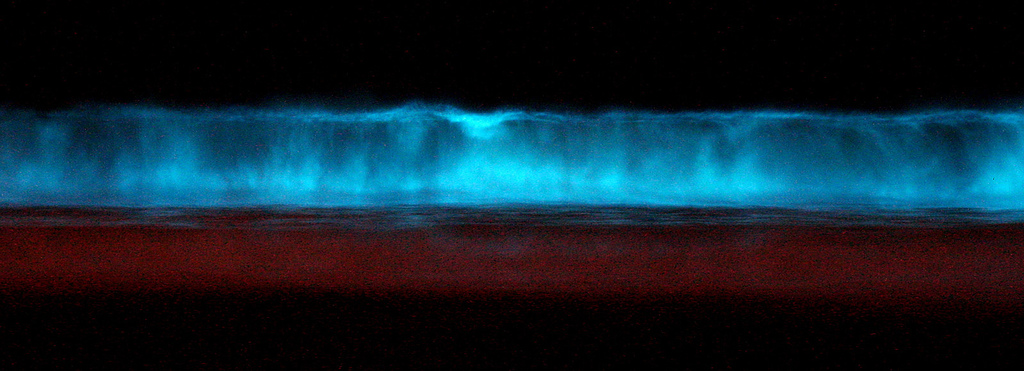

The problem is that the detachment from the body that seems inherent in religious discourse about pornography means that we're talking about something more than (or other than) porn when we talk about porn. John Ashcroft's notorious covering up of nude Greek statues in the Department of Justice HQ, Janet Jackson's wardrobe malfunction, my own recent Costa Rican beach epiphany can all be gathered up by the same Puritanical net - with Ashcroft seen as a hero for the cause of what it means to be moral, Jackson as a cultural whore (not my words), and me as a kind of weird half-man, half-alien, who needs to be naked in the Pacific Ocean under a starkly moonlit sky to find himself. The paradox here arises when it becomes clear that religious institutions and individuals have sometimes been pretty holistic in their approach to sex and the body - images on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the conversion declaration of St Francis of Assisi, the Metaphysical poets, and more recently the writings of people like Mike Riddell and Stuart Davis. But it's rare today for a religious leader to publicly affirm sexuality in all its earthiness and wonder, messiness and delight; it's easier to talk about what we want to stop, the fear of libidinous floodgates opening to unleash meta-level bodily fluids to sweep us all to a red light district hell from which no good can come. The irony, as far as I can see, is the fact that the sexual repression that characterises so much religious discourse and experience is already a kind of hell; just as much as the places where sexuality is but a commodity in games of pleasure and economic necessity alike.

What I mean is this: when religious institutions talk about the evils of pornography, but hide the rest of what might be said about sexuality under a bushel, what they're usually talking about is at least partly fear of the human body. Pornography is problematic, to be sure. But that's not the point. Sexuality and the body can no more be divorced than my sense of humour and the rest of my personality. The 'porn part' of sexuality may well be the shadow side; but for a shadow to exist, there must be a source of light. It's the body and sexuality as sources of light that I wish religious institutions would invest in.

In preparation for the release of

In preparation for the release of  “Your principal concern appears to be that the Creator of the universe will take offence at something people do while naked. This prudery of yours contributes daily to the surplus of human misery.” – Sam Harris, ‘Letter to a Christian Nation’

“Your principal concern appears to be that the Creator of the universe will take offence at something people do while naked. This prudery of yours contributes daily to the surplus of human misery.” – Sam Harris, ‘Letter to a Christian Nation’