There are things that existed before we did, and will be here after we leave. Koyaanisqatsi (from the Hopi language, meaning ‘life out of balance’, and released this month on Criterion DVD and BluRay as part of what I'm voting for as the best box set of 2012) is perhaps the most relentlessly overpowering film about nature ever made; endlessly imitated, never equalled, it could serve both as a prophetic warning and an aid to worship, as we are overwhelmed by the beauty of the earth, and the destructiveness of humankind. It has the power to make you see everything with new eyes – like Neo’s early experience of the Matrix – to feel like you’re looking at the world around you for the first time. I saw it performed ‘live’ once, with Philip Glass playing alongside the projected print – maybe the best experience I’ve ever had in a cinema. It’s dangerously exhilarating to watch, perhaps especially because you have the sneaking suspicion that you’re seeing yourself on the screen. What has been called ‘the illusory nature of created things’ is one thing; but sometimes those created things are pretty good at damaging other created things – and this film is not an illusion. Aboriginal cultures believe that nobody owns the land, and I suppose this is not a million miles away from ‘the earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it’. This film will make you awestruck at creation, whether or not you believe in God, and maybe weep for what we’re doing to it. It's director Godfrey Reggio is a former Catholic monk, and the composer of its remarkable score, Mr Glass is a Buddhist – so if you think knowing something about the authorship of a work of art is irrelevant to how you understand or appreciate it, think again. These guys are clearly devoted to their own spirituality and want to draw us in too. They are amply supported by the cinematographer, Ron Fricke (director of this year's magnificent 'Samsara'); there is no adequate way to describe the photography. The movie has no dialogue; it is simply a journey from un-populated parts of the planet to the mega-conurbations of the industrialized world.

While there is little sign of where human beings have dealt well with what we’ve been given, Reggio wants to show us what went right, what is chaotic and magnificent about the earth before what went wrong. In the opening scenes, he manages to make us see the earth like we’ve never gazed on it before – desert spaces evoking Martian landscapes. One of the biblical writers said that the stones would rise up and worship God if we people do not; and it looks like that’s just what they’re doing in these early sequences. We see sand dunes looking like corrugated cardboard, and cloud formations like tidal waves or explosions, convulsions of white light that look like they pose a danger to us, followed by fields of surreally-coloured flowers that consume our own field of vision. These scenes are reminiscent of the amazing ‘Rite of Spring’ Sequence in Disney’s 'Fantasia', but before we get too comfortable with the images of beautiful nature, we are brought down to the level of the human with a whimper.

We see sunbathers overshadowed by power stations, mechanical diggers looking like mythical monsters, and in a sequence where Fricke manages to actually photograph heat, planes waltzing with each other on the highway, as thousands of cars (looking like tanks) take cover. It’s funny seeing the old cars (the movie’s 30 years old), but the metaphor has more meaning now than ever. People rush on with their existences. And they destroy things – apartment blocks collapse like sandcastles, pork is fed into a processor from which is ejected an excuse for food (you may never eat a sausage again after you see how they get made on production line), and rockets explode on take off. Bombs are photographed as if they’re sex objects (which, of course, for some people, they seem to be); the fetishisation of violence is simply portrayed, with the audience free to make its own judgement.

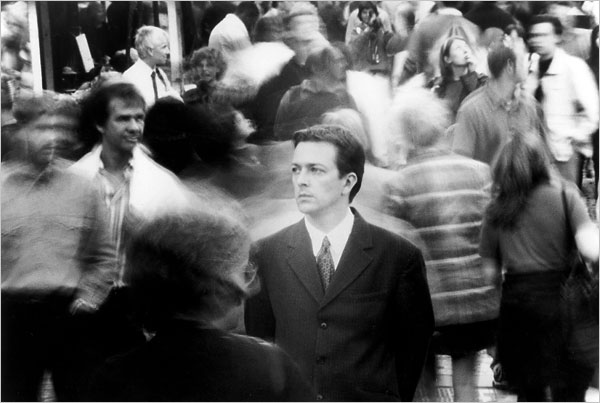

The rest of the film focuses on you and me, as we follow people, often in intrusive closeup, through city life. The people are running around like members of a particularly neurotic ant colony, but one somehow less than the sum of its parts; those shown in close up look like they’re made out of plastic, as if they are on display to be laughed at; the film seems to be asking what is left of their humanity. The violence of food court normality seems to indicate Reggio’s plea that we might once again engage in the sacrament of eating together, taking time with each other, instead of working soulless jobs to make just enough money to buy things we don’t need.

And so it goes, and so it goes, and so it goes…Why do people want to live like this? Why do we accept it? It seems that it’s not enough to destroy nature by what we build, but we don’t even build the right things, or the things we need; and when we’ve built them, we destroy them also. Shadow religion must bear its share of responsibility for the dangerous instant throwaway culture we’ve inherited. There are plenty of unhealthy apocalyptic theories that imply it’s ok to let the world go to seed because it’s all eventually going to end anyway. But what if the first commandment recorded in the Hebrew Scriptures - a document worth paying attention to, even if only for its value as a record of what people used to think - God gave – ‘subdue’, or look after the earth – is still the prime directive for humankind? What if our core task is not to prepare the way for some kind of spectacular Second Coming (which tends to frighten and confuse people more than it brings hope; and, although some might find this hard to believe, the theory of the Rapture proclaimed in recent populist Christian fiction is just that – fiction, with little or no relation to a rigorous, well-informed reading of Scripture and church history) but rather to become more human, and in that becoming, make way for Jesus, the Son of Man, or Quintessential Human to be born in all our lives? To put it another way, while we don’t have to be Luddites or Amish to be Christians, though it might help, and it certainly doesn't mean that we shouldn't ask ourselves exactly what would Jesus drive?

Does Koyaanisqatsi reflect anything of the goodness of humankind? Maybe not, but that is the point of the film; Reggio is prophesying to us that our failure as a race to be good stewards of the earth has left us in dire straits, and unless we do something about it, we will have nothing left to steward. We are a broken race of people so often living in fear – we see a man by his window, a woman stepping over a fire hose, people getting into an elevator, relentless television evangelists pronouncing violent rhetoric, an old woman’s hand reaching out for a touch, a homeless man counting coppers in his palm, with an unexplained bruise on his forehead, while a choir laments on the soundtrack. When the people get into the elevator, you want to cry out to them to stop, but you feel that it’s too late; it's a reminder of Ezekiel’s words about the need to warn our human brothers and sisters of the enemy’s approach, or their blood will be on our hands. There are some examples of how human beings can get it right – an heroic firefighter, people smiling, enjoying each other’s company, kids playing games together; but, on the whole, this is not a film about the lighter side of life. For me, the most striking image is the close up of the man with the saddest face I’ve ever seen – he looks like Max von Sydow on a really bad day. You want to reach out and touch him, to take him by the hand and tell him that it’s going to be alright, that whatever catastrophe of broken relationships or illness or mental dysfunction that has been visited upon him, you will take responsibility to help heal.

But the world isn't just broken - I'll go with the tradition that says it is also good, and can be redeemed. And in that light, Koyaanisqatsi could be the content of a reflective worship service; an attempt at restoration of the church’s lost tradition of lament. It’s so beautiful – as its creator says, a terrible beauty, an awesome beauty, the beauty of the beast – it could make the heart break. Its most shocking aspect is the acknowledgement that Westerners are prima facie guilty of idolatry – that the horrific truth that faces us is the possibility that what we most value is a monster that eats the earth. It’s more like a symphony than a narrative film, and we should be left in no doubt of its message – that there is always a limit to human endeavor, and we need something bigger than our best ideas of God to rescue us. We end with a vision of Hopi cave paintings, and the disturbing prophecy of a future ‘Day of Purification’ on which the world will be purged of those who seek to destroy it. Those who were here before us have left their mark of epochal wisdom. Koyaanisqatsi is a word that has no English equivalent, but can be loosely translated as ‘life out of balance; a way of life that calls for another way of being’. How much more resonance with a religious story of redemption do you want? Reggio says that the Hopi words help him because ‘Our language is in a state of vast humiliation’ – it is no longer adequate to describe the horror of the underbelly of our existence. Everything that we consider sane was a mark of insanity for Aboriginal people. Like the foolishness of God being wiser than the wisdom of humans, we need to consider if our ‘normal’ ways are actually distortions of what’s best. We need to find new ways of being, but perhaps we will only be able to do so when we have found the courage to simply talk about what we are becoming.

It is likely that you may go away from this film with a sense of despair (it might not be the film to watch last thing at night; although the most frightening thing about it may be the clothes people liked to wear in the 80s). But, after you have let it rest in you for a while, you may recognise its prophetic spirit. You may remember the lonely people, and realise that these are those whom we are called to serve, to love, to welcome. Human beings, one to another, are gifted with the power to heal the broken, to bind up wounds, to mend divided communities, and to participate in the redemption of the earth. The camera seems to look into the souls of its subjects, which is a necessary step if we are to heal each other. Reggio has said that, having entered a monastery at age 14, he grew up in effect in the middle ages, which was bad and good at the same time, and gave him a special preparation for life, a life of humility and service and prayer. I think it gave him a special preparation for cinema too; perhaps all directors should spend time in spiritual contemplation before they attempt to portray what it is to be human; in fact, I suspect most of the best do just that. At the end of Koyaanisqatsi, we will have been exhilarated and challenged; our field of vision will have been consumed by terrible beauty, our ears will have been honoured by music that seems to come from another world, our very senses will have been possessed by something that we have not seen before. And this is all good. But the question is, when we try to recall the human ant colony we just saw on screen, do we recognise ourselves in their faces? Those who have ears to hear, let them hear…