Male Violence, the End of Empire and 'Lawrence of Arabia'

I'm seeing David Lean's 'Lawrence of Arabia' tonight at the Carolina Theatre in Durham. Again. I've been fortunate to see it in 70mm (if you don't know what 70mm is, let's just say that it's what movies used to look like when you were a kid - HUGE and CLEAR and EPIC; and it's a format that's very rarely used these days). This film is approaching fifty years old, but the last time I saw it - a year ago - it seemed so sure of itself and its themes so universal that it could have been made anytime.

I'm seeing David Lean's 'Lawrence of Arabia' tonight at the Carolina Theatre in Durham. Again. I've been fortunate to see it in 70mm (if you don't know what 70mm is, let's just say that it's what movies used to look like when you were a kid - HUGE and CLEAR and EPIC; and it's a format that's very rarely used these days). This film is approaching fifty years old, but the last time I saw it - a year ago - it seemed so sure of itself and its themes so universal that it could have been made anytime.

Most of us who know it from TV screenings on wet Saturday afternoons, or because our grandparents told us about it may too easily disregard it; seeming like an artefact from the pre-CGI, pre-Tarantino, pre-indie witticism past. But if what is past is prologue, then this film - about war, and the effects of war on those who try to make it happen - may demand our attention.

This is a film that evokes the end of the British Empire, and therefore the potential end of the concept of Empire itself; even though it's set during the first world war, it was made in 1962, by which time the notion of one monarch somehow ruling the world was fading into memory, and post-colonial theorists were beginning to make the case that Empire was a bad idea to start with. The place where I was born and raised was about to take on the mantle of the last vestige of this Empire, and some of its people were about to take a leaf out of the revolutionary playbook that had been put to such awful use in places like Algeria, while tragically ignoring, avoiding or de-emphasising the tactics of the non-violent revolutionaries of India and the US Civil Rights Movement. Turns out that those who wanted to hold onto Empire, and those who wanted to overthrow it were both wrong.

Killing people to prove that injustice is wrong may be the most contradictory paradox. To keep Northern Ireland in the United Kingdom, the government turned it into something like a security state; to make Ireland free, Irish people killed other Irish people; to keep Ulster British, British people killed other British people. For decades. And then we came inexorably to the conclusion that Empire (or an Independent Ireland) didn't matter as much as ensuring that every citizen has a stake in the governance of the society; that equality of opportunity should be enshrined in law; and that the only way to bring a violent conflict to an end is for someone to stop shooting first.

'Lawrence of Arabia' may have stirred a kind of nostalgic patriotism among British audiences in the 1960s - it is, on the surface after all, largely about how an English soldier helped Arabs defeat the Turkish army. But it's much more subtle than a simple flag-waving exercise - its examination of Lawrence's psyche is deeply subversive in that it admits something that popular war movies tend to ignore: that killing can be addictive. It foreshadows the recent amazing film 'The Hurt Locker' in Lawrence's admission that he 'enjoyed it' when called upon to execute a misbehaving nomad - but it actually goes further, in that it's clear that while he enjoyed it, he doesn't enjoy the fact that he enjoyed it.

He's deeply troubled, and at the end of the war is no longer the integrated, Noel Coward-esque wit we saw at the beginning. Lawrence has 'a funny sense of fun' - and David Lean had a very sharp sense of the brutalisation that so many men embrace in order to feel alive, and how we have mislaid other rituals that used to pronounce and even convey adulthood. The most well known line in the film is probably 'Nothing is written' - Lawrence's refusal to endorse the fatalism of pre-rational ways of doing religion; the human being is supposed to act on history, not be swept away by it. I don't watch 'Lawrence of Arabia' to be thrilled by the violence or excited by the military 'victories' - they didn't last; and they certainly didn't produce a lasting peace in the Middle East; geo-politics is still dealing with the legacy of how Britain and what became Saudi Arabia tangoed a hundred years ago. I watch it because, apart from the fact that it moves with grace and notes and a propulsive narrative, and imagery that has never been repeated, it tells the story of a man who faced a crisis, made a choice, and changed the world. His was dangerous change. I need to be reminded that I am subject to the male addiction to transformation through outer violence; because if I don't find a way to transform that violence into something that neither seeks to wound nor colonise others into my own little Empire of Self, my life will be dynamite, and not in a good way.

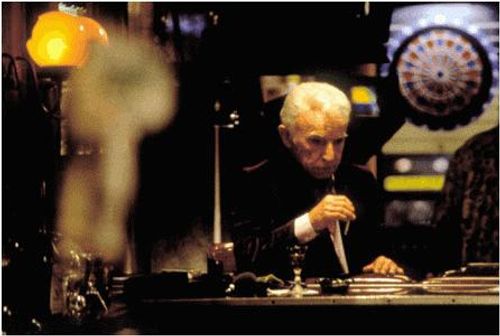

You know Henry Gibson. He's one of those character actors who beefed up everything he was in, and indelibly so. Fully worthy of

You know Henry Gibson. He's one of those character actors who beefed up everything he was in, and indelibly so. Fully worthy of  He helped anchor work as various and memorable as 'The Long Goodbye' (which

He helped anchor work as various and memorable as 'The Long Goodbye' (which  I've been slowly captivated over the years by the films of Andrei Tarkovsky - the last scene of his

I've been slowly captivated over the years by the films of Andrei Tarkovsky - the last scene of his  And so we turn to the news on a Monday morning: Things are going just fine in the world of dumbed down culture – I just heard a story on NPR suggesting that the writers of Jay Leno’s

And so we turn to the news on a Monday morning: Things are going just fine in the world of dumbed down culture – I just heard a story on NPR suggesting that the writers of Jay Leno’s