I gave this talk a while back at the Reel Spirituality Conference, at Fuller Theological Seminary. Some folk have been asking me to explain how I engage with cinema, so here are a few thoughts:

There’s a stunning moment toward the end of ‘Make Way For Tomorrow’, Leo McCarey’s unimpeachable 1937 masterpiece, and the film that Orson Welles described as the saddest movie ever made, when our heroes - and victims, Barkley and Lucy, ageing parents reduced by the Great Depression to not being able to afford their home, and about to be split up by their grown children, none of whom are willing to care for them meaningfully, spend an afternoon reminiscing about their honeymoon. They share a meal at the hotel they had visited 50 years before, they recite poetry to each other, they decide to dance together. The audience knows that this is quite possibly the last time they will see each other. At the dinner table, Barkley and Lucy, played by Victor Moore and Beulah Bondi do something usually associated with Brechtian theatre; or a more recent postmodern sensibility. They turn toward the camera, and stare piercingly into our eyes. Into our souls. They are asking us to visit with them, to sit still for a second and really identify with them, to actually face their sorrow, and our complicity in the sorrow each of us may cause in the course of a lifetime. It’s an astonishing moment; ‘Make Way for Tomorrow’ may well be the saddest movie ever made.

Make Way for Tomorrow

We may also feel that today’s conference has been an embodiment of the kind of moment captured on film at the end of ‘Make Way for Tomorrow’ - with those of us whose vocations as critics seem to be being forced aside by the callous children of social media, non-paying super-blogs, and film studios who don’t care what we think. To this, I would want to offer a note of caution - there’s something else about tomorrow that the movies teach us; and all is not lost. We’ll get to that teaching on tomorrow later; for now, let me tell you a story about myself.

In the Beginning...

1. The places that matter to me are frequently not real. They’re places I’ve seen dancing on a white screen, animated by dusty light in a darkened room. They’re places I’ve been to without leaving the (dis)comfort of a plush red seat with no legroom. They’re places that seem bigger than real life.

These places exist, because In The Beginning, the Creator, in the form of two French engineers, down on their luck, perhaps too dependent on Maman, and not sure what to do with their lives, had an idea. On a winter’s night in the early 1890s, it occurred to them that what the world in mid-Industrial Revolution needed most was to have the opportunity to watch pictures dancing with light and dust. The well-being of the planet could be nurtured by thirty feet high images of men with guns, women with perfectly fake breasts, and young men having sex with cherry pies. That was the gift of the Lumiere Brothers. If you visit the cemetery where they’re buried, you can find their grave easily – it’s the one with the neatly tilled soil – they’ve turned over in shame so many times that it always looks like their plot was freshly dug.

In spite of the sometimes embarrassing nature of their legacy, when I reflect on what makes me human, or at least what makes me feel human, because, God knows, there’s enough out there that tries to deal death to any sentient notion of experiential human-ness, I find my thoughts turn, more often than not, to the movies.

I think my soul finds rest when the curtain goes up, in the way that, for some people, watching football on television can make them feel at home in themselves. I often feel whole when I’m in a cinema; partly, I think, because it connects me with the innocence of childhood, and partly because, for the two hours or so that I’m in that space, nothing else can touch me. One of the characters in ‘Death of a Salesman’ iterates, even lives by the shibboleth ‘attention must be paid’, that’s a call so powerful that it can kill – and I wonder if it’s also because the film I’m watching has no choice but to pay attention to me that I like to go to the movies so much.

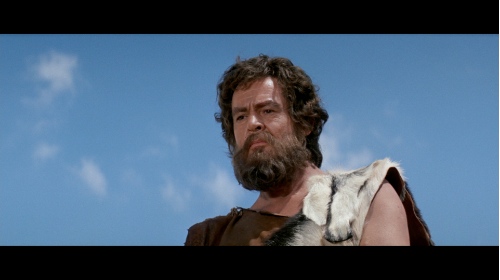

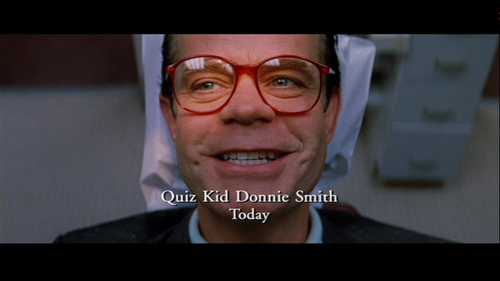

And every once in a while, someone on the screen says or does something that makes me feel understood, as when William H Macy’s Donnie Smith in ‘Magnolia’ cries ‘I really do have love to give, I just don’t know where to put it’, or when Gene Hackman’s master thief in David Mamet’s ‘Heist’ explains how he gets away with it: ‘I’m not smart, I just imagine what people smarter than I would do in the same situation and then I do that’, or when I watch ‘The Wizard of Oz’ every December and am reminded that my fears are just an old man behind a curtain, who only has the power I give to him.

And if the notion of using a fairy tale wizard as a psychological tool strikes you as odd, I guess I should say that I have long believed that the way cinema portrays life doesn’t have to be ‘real’, as long as it’s not fake. But my reasons for seeing film as something worthy of an investment of precious time are more than psychotherapeutic; they’re sociological, and perhaps even prophetic. Arthur Miller, author of that same attention-giver ‘Death of a Salesman’ was described on his death by Time magazine as a ‘slayer of false values’, and the best cinematic art does just that. Chuck Palahniuk told me once that he wrote the section in ‘Fight Club’ about IKEA catalogues as postmodern pornography because he wanted to satirise his own superficiality – the book is about the author’s own attempts to break free from mediocrity. And so, failing thought it may be, is this paper. And the films I most give a damn about are the ones that give a damn about me – or at least about people generally, and the struggle to be human in a technophiliac world, driven by the forces of what it's too easy to call (because it's real) the military-industrial-media-entertainment complex.

2.Martin Scorsese famously spent his early years in a movie theatre because of asthma; I did it because I didn’t like playing rugby – and that’s the only other thing that was available on bleak Northern Ireland Saturdays. I wonder now whether or not I would have been any good at rugby had Marty McFly not gone back to the future in such compelling fashion.

My Childhood Mentor

It was the first movie I saw more than once at the cinema; and on the day my elementary school exam results were issued I chose to see it a third time rather than take a family day trip to Dublin, which at the time was the most exciting place I’d ever been. That kind of commitment is a bit like that of the smoker who can’t afford to buy groceries, but can always find enough money for cigarettes. Friends and lovers alike have found my willingness to drop everything in favour of the movies endearing, at least the first time, although the charm of considering cinema more important than real life soon wears off.

There are angels on the streets of Berlin.

But that’s only because the world is made up of two kinds of people - those who get movies, and those who don’t. The first kind, my kind of people, can sit in the enclosed darkened room at any time of day, and get excited when the lights go down, no matter what is about to appear on screen. We travel half way round the world to visit film festivals to see movies that will be released at home in a few months anyway; we pay good money to go to Berlin for a morning just to see the statue the angels perch on in ‘Wings of Desire’; we fall into ourselves with delirium when we catch a glimpse of Isabella Rossellini on the street; we stay up late to watch films we’ve only vaguely heard of because our fellow cinematic nerds have said the cinematographer ‘has a wonderful eye’, or that the movie influenced the mid-wave of the post-apocalyptic Mongolian agricultural documentary movement, or perhaps merely because someone told us the director’s dog has a great bark.

3. For what it’s worth, this is what I think about the power of cinema: it makes us imagine something bigger than ourselves. I’m not sure I can do that with words, but not being fulfilled by the real temples of organised religion has allowed me to kneel at the altar of the white screen and demand that it answer my life’s questions.

Smaller in Real Life

Smaller in Real Life

I think about the magic of cinema, the God’s-eye view we have of those on screen; and how when I met a Big Star I felt weird because he wasn’t as tall as he should be. Given that that would be around 18 feet, this shouldn’t have come as a surprise, but inasmuch as Al Pacino’s character in Michael Mann’s ‘Heat’ believes that holding onto his angst keeps him sharp, I suppose for me, holding onto my naivety might keep me in touch with the kind of innocence of which a cynical world needs a great deal more.

I think of a hundred heroic films that made me feel like anything was possible, or romantic comedies that taught me something about love, or dramas that helped explain the meaning of life.

I think of ‘Magnolia’ and wonder at its capacity for squeezing in what is wrong with modern North American middle class life, and how the opportunity for redemption cannot be engineered, but must simply be received. And 'Broadway Danny Rose', and 'Close Encounters of the Third Kind', and 'Limbo' and everything else John Sayles has ever made.

I think of ‘Jean de Florette’ and ‘Manon des Sources’ and how they begin as innocuous dramas about a dispute between neighbours, but conclude with you being terrified for the characters, and you want them to love and not destroy each other, because they make you think about how knowing one extra piece of information about a person can change everything. The fearful miracle is that it can make you love instead of killing them. And 'Fanny and Alexander', and 'Au Hasard Balthasar', and 'La Regle du Jeu' and 'The Grey Zone' (by the most undervalued/underrated/underknown director working today).

I think of the best double bill I ever curated - two films that have far more in common that you would think, both stories about the search by ordinary people for a sense of purpose and success, centred on ‘making it’ in the film industry, and raising issues of what might get sacrificed along the way, these two films which are, of course: ‘Mulhulland Dr.’ and ‘The Muppet Movie’. Trust me - they belong together.

I think of the best double bill I ever curated - two films that have far more in common that you would think, both stories about the search by ordinary people for a sense of purpose and success, centred on ‘making it’ in the film industry, and raising issues of what might get sacrificed along the way, these two films which are, of course: ‘Mulhulland Dr.’ and ‘The Muppet Movie’. Trust me - they belong together.

I think about how sometimes I’d prefer the magic of cinema to stay where it used to be – in my heart; and I wish that I didn’t have to force myself to become innocent every time I see a movie – I wish for the time when there was no difference between my belief about what was possible, and Hollywood’s vision. I wish for a time when I didn’t have to work to put myself in the frame of mind that believed in the possibility of hope.

And I think about going to see Julian Schnabel’s ‘Basquiat’ in a Kansas City art house on a day in the summer of 1996 when it appeared that only single men were allowed into the theatre. Thirteen of us, sitting alone, dotted around the cinema, enraptured by the imagery that told of this broken artist and Reagan-era Warhol cohort. The film ends with the telling of a medieval myth about a prince locked in a tower by his evil relatives; to alert the local peasantry to his predicament, he bangs his crown off the wall, but they hear this only as music…it was an image with the potential to become the definition of cliché, but to us in the audience, it spoke only of the way we feel about the world. As Henryk Gorecki’s ‘Symphony of Sorrowful Songs’ reached its long crescendo and the prince banged his head harder, a guy in the front row of the Kansas City theatre flung his arms in the air, and held them there, as if this were a worship service. This was worship - of a kind; worship of the divine so many of us still want to believe in or hope for, and perhaps also of the extraordinary creative urge of which humans are sometimes capable.

‘Basquiat’ is the kind of film that might make the Lumiere Brothers feel their endeavours were not wasted; and this is germane to our discussion for one simple reason: I would not have gone to see ‘Basquiat’ if it had not been for film criticism. I would not have gone to see ‘Basquiat’ if it had not been for Roger Ebert, who at the time of its release wrote the following:

‘Anyone who has ever painted or drawn knows the experience of dropping out of the world of words and time. A state of reverie takes over; there is no sensation of the passing of hours. The voice inside our head that allows us to talk to ourselves falls silent, and there is only color, form, texture and the way things flow together.

There is a theory to explain this. Language is centered on the left side of the brain. Art lives on the right side. You can't draw a thing as long as you're thinking about it in words. That's why artists are inarticulate about their work, and why it is naive to ask them, ``What were you thinking about when you did this?'' They have given it less thought than you have.’

And this is why the critic is necessary. Because the function of the critic is not the same as the function of the artist. Criticism, of course, may be artful, just as film-making is sometimes artless; but the primary function of criticism is closer to that of spiritual director than poet. In short, if we are ultimately all one person made in the image of God (that's a hypothesis, of course, but you don't have to agree with it to keep reading), and the task of being human includes freeing ourselves from mutually exclusive interpretations, or what Freud in Nicholas Meyer's 'The Seven Per-cent Solution' calls 'less finite solutions' to human problems than killing each other, and to become more than the sum of our parts by hearing the voices of - and thereby honoring the image of God in - others, then the role of the critic is supremely important: because critics show us what it is that we’re doing.

This matters because - obviously - art matters. And, as Ebert said in his ‘Basquiat’ review, artists don’t always know what it is they are doing.

For instance, ‘Shutter Island’, for me, the most artful and theologically important film released in 2010 (and by di Caprio's presence evidence that massive celebrity does not necessarily preclude high art's potential) speaks profoundly about the lament that America needs to sit with if the wound of 9/11 and the projected shadow that followed are to be integrated into the national psyche; but I’m not sure than even Martin Scorsese knows that. It takes the hermeneutic community that becomes possible when people who didn’t make the film but live as informed audience members to reflect back on what the film may mean so that readers might be provoked to think further about the value of this art object in their lives.

Because none of this makes sense apart from everyday human experience. I project my desire onto the narrative arcs stewarded by films as various and diverse as

‘Andrei Rublev’,

‘Field of Dreams’,

‘Field of Dreams’,

and ‘The Exorcist’.

As Proust wrote of characters in novels, I see myself revealed in cinematic representations of 15th century Russian icon painters, 20th century hippy farmers in Iowa, and ancient but new Catholic demon expellers. Now, I don’t paint icons, and I don’t farm, and the last time anyone threw up in my face it wasn’t Linda Blair - but the archetypal journeys of Andrei Rublev, Kevin Costner’s hippy farmer, and Jason Miller’s Fr Karras in The Exorcist speak profoundly to me about my own journey.

James L Brooks wrote a line worth the $120 million budget of ‘How Do You Know?’, a film not thought by many to be the revelation of a profound mystery about human existence, but nonetheless worth reflecting on - ‘Life is about finding out what you want, and learning how to ask for it’. This may sound selfish at first, but understood more thoughtfully could be seen as a postmodern variation on what St Augustine understood as the injunction to ‘love God, and do what you want’. And all fiction is about this: people finding out (or not finding out) what they want (or don’t want) and learning how to ask (or not ask) for it. All fiction is reflective of the nature of being human: because to be human is to be a storyteller. We tell the story of our lives, and this story circumscribes for us what we believe to be possible. Film-makers tell us a story about their lives, and their vision of what is possible in the world. Critics are supposed to interpret this story. It was ever thus. This happened, surely, in biblical times - Jesus was a critic of his social order, and of the stories people believed and lived from. It happened at regal courts when jesters whispered satire in the ear of the king. It happened in 19th century Denmark when Soren Kierkegaard suggested charging a fee to theologians who wanted to attend his bible studies, as they/we make our living off the crucified Christ, we should be prepared to pay for the privilege of participating in the Christian community. It happened in the 1970s when the New Zealand poet James K Baxter quit his high-paying job as a university professor to found a community in the wilderness, the sole entry qualification to which was a willingness to admit personal brokenness. And it happens today, every time film critics manage to bypass snark and shortcut to share humbly and with grace our response to the art objects we are privileged to see before the public do.

I want to conclude by acknowledging the economic precariousness we face as critics. Some of us are lucky to be paid to work full-time as film critics. I am not one of them. Some of us are lucky to be paid to work full-time as theologians. I am not one of them. But as I think that all of us are called to be both critics and theologians, I get to do the work, whether I get paid for it or not. The economic model that has sustained film criticism (and academic theology) for the past half-century will give way to something else. If I ruled the world, I’d want that something else to be reminiscent of an egalitarian locavore non-nuclear family community, where we work and live together, earning what we can from meaningful income-generating work, sharing our goods with each other, and sitting round tables talking about what the latest

Michael Haneke, or

Michael Apted, or

(even) Michael Bay

says about the nature of being. But that’s a few years off.

For now, let us recognize this, with humility:

It’s a high calling, to be a critic. I don't intend that to enlarge our egos - there are many high callings, chief among them in my view is that of getting to be a human being, so recognizing the importance of the act of criticism is certainly not any kind of avowal of superiority over others. But it is a spiritual discipline that can assist ourselves and others in learning how to take that universal calling - being human - more seriously, and to understand it better. In the sacred act of call and response that we and film-makers are stuck in together, whether we like it or not, criticism is half the work. They call, we respond. We do not best serve our calling by resorting to easy snark, personal insults, or by equating the task of criticism with just criticizing.

Critics have a role to play in helping the world tell its own story. We have privileged access to the newest variations on that story, every time we go to a preview screening. And we get to help hold cultural, psychological, and spiritual memory.

We can look back on ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, and write about how it still feels ahead of its time, and more than that, speaks profoundly to our hope that ancient truth doesn’t need to be adapted: in short - love does conquer all.

We can help our audience respond to ‘Shutter Island’ or ‘Once Upon a Time in America’ by saying how each feels like a religious icon of lament, and that if you don’t learn to face the darkness of your past, you will simply keep hurting yourself, and everyone around you.

We can declare from the rooftops that it is entirely consistent to be thrilled, moved, and even inspired by the horrific sacrifice in ‘The Exorcist’

and moved by the end of ‘ET’

and stimulated to be more compassionate for the suffering people of the world by Atom Egoyan's 'Exotica',

and moved by ‘The Elephant Man’

and provoked to think about the relationship between dreams and reality by ‘Eyes Wide Shut’

and historically challenged by the too-recently departedTheo Angelopoulos’ ‘Eternity and a Day’. And that’s just a few films beginning with the letter E.

In short, critics can nurture a space in which people can find their own way toward interpreting the art they are watching, and to dialogue with themselves about what it means to be human. This is a high calling indeed. We owe it to ourselves, and to our calling to respect the difference between criticizing and critique; between snark and thoughtful challenge; and between personal insult and encouraging improvement. It’s a high calling that doesn’t depend on money, isn’t determined by the market, and isn’t even about whether or not we get to do this for a living. It’s about who you are, how transparent you are willing to be with your readers about how your projected desires found (or didn’t find) resonance on the screen. In my judgement, there are only two qualifications: you need to know something about movies; and you need to want to be more human.

In the new world of the democratization of criticism, we may feel threatened by how 140 characters or less might have the power to undermine our work. But as the Franciscan activist priest Richard Rohr says, the best response to the bad is the practice of the good. Social media doesn’t have to be a threat: in fact, it actually opens up space for more authentic dialogue between critics and our audience, and between critics and film-makers than was ever previously possible. So please, tweet away. Facebook your desire to live differently after seeing Gaspar Noe’s ‘Enter the Void’; blog how your hopes and dreams are in a recursive relationship - shaping and being shaped by - your experience of Abbas Kiarostami or Steven Spielberg or Wim Wenders or Edward Yang or Hirokazu Koreeda or Mike Leigh or Jim Jarmusch. And, if you can, make money from it. But above all, be faithful to the calling of being a critic in the context of something called the arts and humanities: your calling is to help rehumanize the world. And don’t be afraid of tomorrow, because if what Elvis Mitchell earlier called the boringest and most racist movie of all time - and therefore one of the most important - teaches us anything about tomorrow, it is that tomorrow is another day.