The Most Important Film I've Seen This Year

I recently had the chance to see ‘Hunger’, the astonishing feature film debut of the visual artist Steve McQueen, which compelled audiences on its release last Autumn, and is now available on DVD.

I recently had the chance to see ‘Hunger’, the astonishing feature film debut of the visual artist Steve McQueen, which compelled audiences on its release last Autumn, and is now available on DVD.

The political responses to the film were predictable – but the film itself was not. In the first instance, it is not, as was assumed, a film primarily about Bobby Sands, or even about the 1981 hunger strikes in general. No historical knowledge of the socio-political context is necessary to understand or appreciate ‘Hunger’; in fact it’s likely that people outside northern Ireland will experience the film as a work of moral philosophy, while we locals may be unable to divorce ourselves from the traumatic memories of violence and sorrow that so many of us harbour, whether we know it or not.

‘Hunger’ is about the descent into dehumanization that every violent political conflict includes: the reduction of other human beings to ‘types’ and not personalities, sociological cohorts and not individuals with hopes and dreams and fears and pain. In the film this descent has already taken hold; but we know that in our own society it began as such a reduction, and continued to form part of a deceptive and recursive narrative that, our history has shown can, unless it is arrested by a non-violent negotiation, end with genocide.

The film is in two parts, the first of which focuses on the daily existence – to call it a life would be an overstatement, it being so full of emptiness that it can’t be described as a humane experience – of a prison officer played by Stuart Graham (a magnificent portrayal of broken and brutal northern Irish masculinity). He lives in a tidy middle class Protestant shell; with a quietly terrified wife, eating the same fry for breakfast every day, life regimented by the morning hand and face wash, the surreptitious pulling back of the curtains, the look under the car, the Puritanical schoolboy folding of tin foil sandwich wrapping, the punching he meets out to dirty protest prisoners, the tidiness of the flowers brought to his mentally frail elderly mother, ultimately leading to one of the most horrifying images I’ve ever seen in a film.

The second half begins with a long dialogue between Bobby Sands and a priest, tossing back and forth the question of the morality and purposefulness of the hunger strike. This scene has been acclaimed by critics for taking such a long hard look at one thing: why someone would choose to die for a political cause. Sands, as played by Michael Fassbender (it’s difficult to find adequate superlatives for his performance, so enveloped by the idea of what a human being would go through in starving to death), would call it a human cause before a political one; and perhaps substitute the word ‘inevitability’ for cause – so driven by what he sees as the forces of history to take this stand.

And after the talk, the agonizing death. In this, as in the rest of the film, McQueen is both unsparing and subtle – elliptical scene giving way to elliptical scene, a lot of conversation followed by periods of almost silence, a memory sequence of Sands running as a child. And then, it’s over; fade to black, a caption telling us how many died in the hunger strike, and how many prison officers were killed during the period, and how the prisoners’ demands were met.

For me, ‘Hunger’ might be the most important film yet made about northern Ireland and our shared trauma. It is also the least one-sided (that doesn't mean it is without prejudice; and it's certainly neither a perfect film, nor an attempt at telling the whole story - none could, of course. But for those of us who want our stories to honour the truth of the victims of violence without denying the brokenness of our society, 'Hunger' is a start. A harrowing start that I wouldn't recommend to everyone, but a start nonetheless.) No film has taken more seriously the horror of the taking of life by paramilitaries in the Troubles, nor the brutalization of some citizens by the state. No film has more clearly stated that all violence against the person requires dehumanization; and that such dehumanization will always diminish the credibility of the cause (ostensible or real) of those carrying it out. No film has upset me more. And no film about my home has given me more hope. I understand those who say they would prefer such films not to be made – that they stir up painful memories, or focus too much on those considered combatants rather than non-engaged citizens; but this film does not set out to lionize or demonise anyone. It simply states what should be obvious, and a central part of what people who take being human seriously might be called to embrace: when one suffers, all suffer. You can’t kill a person without tearing a part of yourself.

What You Thought You Always Knew

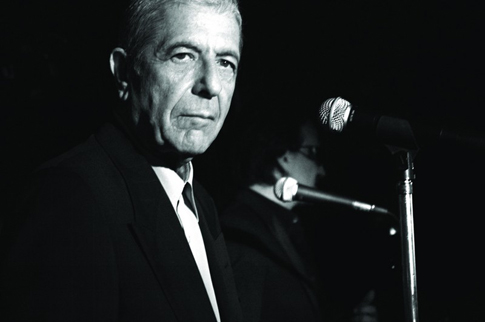

What You Thought You Always Knew It’s been a strange few weeks – suddenly UK politicians have been forced to live like the rest of us (or maybe just a little bit more like the rest of us), senior US politicians are claiming that the CIA lied to them about torture, a Scottish Presbyterian minister is comparing the gay rights movement to Nazism, US radio hosts are implying that President Obama is the antichrist, Tom Hanks is chasing the Illuminati, and Leonard Cohen’s still coming to town. Thank God.

It’s been a strange few weeks – suddenly UK politicians have been forced to live like the rest of us (or maybe just a little bit more like the rest of us), senior US politicians are claiming that the CIA lied to them about torture, a Scottish Presbyterian minister is comparing the gay rights movement to Nazism, US radio hosts are implying that President Obama is the antichrist, Tom Hanks is chasing the Illuminati, and Leonard Cohen’s still coming to town. Thank God.