Andrew O'Hehir has a characteristically smart and helpful review of Terry Eagleton's response to Dawkins and Hitchens (whom he delightedly re-christens 'Ditchkins'; images of an amusing roly-poly pretend intellectual in 'Alice in Wonderland' come to mind) at Salon.

Andrew O'Hehir has a characteristically smart and helpful review of Terry Eagleton's response to Dawkins and Hitchens (whom he delightedly re-christens 'Ditchkins'; images of an amusing roly-poly pretend intellectual in 'Alice in Wonderland' come to mind) at Salon.

When 'The God Delusion' and 'God is not Great' were first published it seemed strange how any thinking person of faith could not agree with the core of what Ditchkins could prove - (drum roll please):

SOMETIMES RELIGIOUS PEOPLE DO BAD THINGS

Anyone with a degree of exposure to the Catholic Worker, the progressive Christian movement, or to take an example from my own locale, the Church of Ireland's reflection on its own sectarianism, and countless other humble attempts to challenge religious imperialism in the terms that Jesus offered already knows that sometimes religious people do bad things; but, remarkably enough (though not enough for Ditchkins) sometimes they also do heroic things, because of their religion.

The fact that these and other books had such cultural impact was another surprise. On the one hand, it was pretty clear that Dawkins knew a lot less about church history and intelligent theology than was necessary to write a credible book about them; on the other, Hitchens, a gutsy writer whose work is often the best take on any particular issue on which he chooses to throw the spotlight, seemed to be more committed to finding the witticisms and aphorisms in religious denunciation than actually saying something we didn't already know.

Terry Eagleton's review of 'The God Delusion' in the New York Review of Books was one of the few pieces published in a 'secular' journal that dared to criticise Dawkins' approach. This has been expanded to book length, and in 'Reason, Faith and Revolution' Eagleton presents the case that, while religion deserves to be critiqued, it's not best done from a place of ignorance.

I was annoyed by Dawkins and Hitchens because they seemed arrogant. Bill Maher's 'Religulous' was even worse - in which a very smart and powerful man asks academic theology questions of people who haven't studied the discipline. You might as well ask me to understand the Latin Mass...But then, well...here's what I wrote at the time:

" I have to pause here, for as I re-read this article I realize that I may have fallen into an ancient trap, and in the process perhaps have simply reinforced Maher’s legitimate concerns. If religious people can be made so easily to look boring, it is partly because we have not articulated a better story. If people of faith are held in low regard because we are seen to be primarily concerned with issues of private morality and Puritanical codes, it is partly because we have not paid enough attention to reason and human experience as guides to interpreting our faith. If, in short, it is easy to portray religious believers as stupid, dangerous, and spineless, it is partly because we have failed to be loving, peaceable, and brave."

There might just be a third way between the twin ideological fundamentalism of Ditchkins and unthinking religion. Terry Eagleton seems to be presenting it, as O'Hehir says,

"Having banished such embarrassing metaphysical matters as God and love to the private sector, and having put its faith in an economic system that seems much less eternal than it used to, Western civilization finds itself in quite a pickle. As Eagleton sees it, late-capitalist society believes in nothing except a limited marketplace vision of tolerance, which has spawned a surfeit of irrational belief systems, from fundamentalism to neoconservative imperialism to do-it-yourself New Age spirituality. He even agrees with the neocons and fundamentalists that we cannot successfully combat Islamist zealotry without any core beliefs of our own.

But the cures proposed by the fundies and neocons are worse than the disease, Eagleton makes clear, while the childish and arrogant idealism of the Ditchkins crowd bears no relationship to human history or contemporary social reality. He sees the potential for hope in a "tragic humanism," one informed by the likes of John Milton and Karl Marx but not necessarily religious or socialist in character, one that "shares liberal humanism's vision of the free flourishing of humanity," but believes "that this is possible only by confronting the very worst." We were sent a man who preached a message of love and we killed him; we were given a beautiful blue-green planet to live on and we killed it. What do we do now?"

One part of Eagelton's response, as O'Hehir has it, is that

"He seeks to reclaim the transformative and even revolutionary potential of Christian faith."

To which I can only say, in the words of one of religion's more recent public faces, who is now fading into post-Presidential twilight, bring it on.

Andrew O'Hehir has

Andrew O'Hehir has The film with this image as one of its centerpieces is currently available to watch for free at

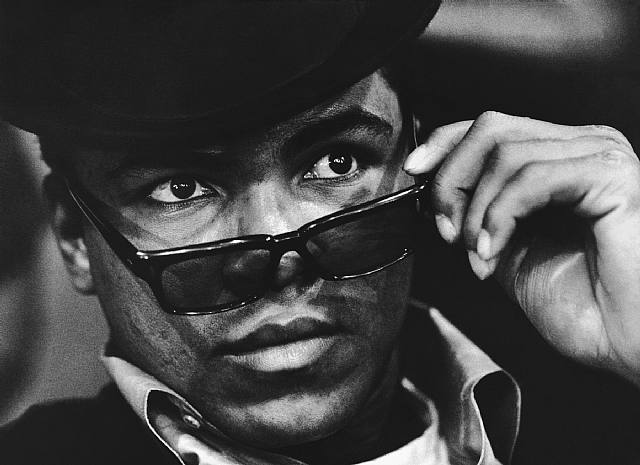

The film with this image as one of its centerpieces is currently available to watch for free at  You’ve seen Eddie Adams’ photographs before. You’ve turned away from the one that made him famous; that of General Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Vietcong prisoner, an image that some people credit with creating a turning point in the Vietnam War. Woody Allen covered a wall with the photo as a way of satirizing the tendency of some artists to wallow in self-pity while the world burns; at least one musician used it as home décor to remind – he says – himself of the tortuous nature of how other people live.

You’ve seen Eddie Adams’ photographs before. You’ve turned away from the one that made him famous; that of General Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Vietcong prisoner, an image that some people credit with creating a turning point in the Vietnam War. Woody Allen covered a wall with the photo as a way of satirizing the tendency of some artists to wallow in self-pity while the world burns; at least one musician used it as home décor to remind – he says – himself of the tortuous nature of how other people live.